ETVMA News

OVER THERE: TENNESSEE AND HER ALLIES IN WORLD WAR TWO

To commemorate the 80th anniversary of D-Day and to acknowledge the great sacrifices undertaken by the “greatest generation,” the East Tennessee Historical Society is holding a three-day conference on the Second World War from 8th of July until the 10th of July at the East Tennessee History Center. The conference will include talks from East Tennessee scholars of the Second World War and will feature international speakers such as Prof. Richard Toye of University of Exeter and our keynote speaker Allen Packwood, Director of the Churchill Archives of the University of Cambridge.

For more information see: https://www.easttnhistory.org/event/over-there-tennessee-and-her-allies-in-world-war-two/

The Battle of Midway in the Pacific

1942: The four-day Battle of Midway began in the Pacific Theater of World War II with over 100 Japanese aircraft attacking both Sand and Eastern islands in the Midway Atoll, a U.S. military area. The U.S. Navy turned the tide against the Japanese naval forces by sinking critical key aircraft carriers in a battle that established American dominance in

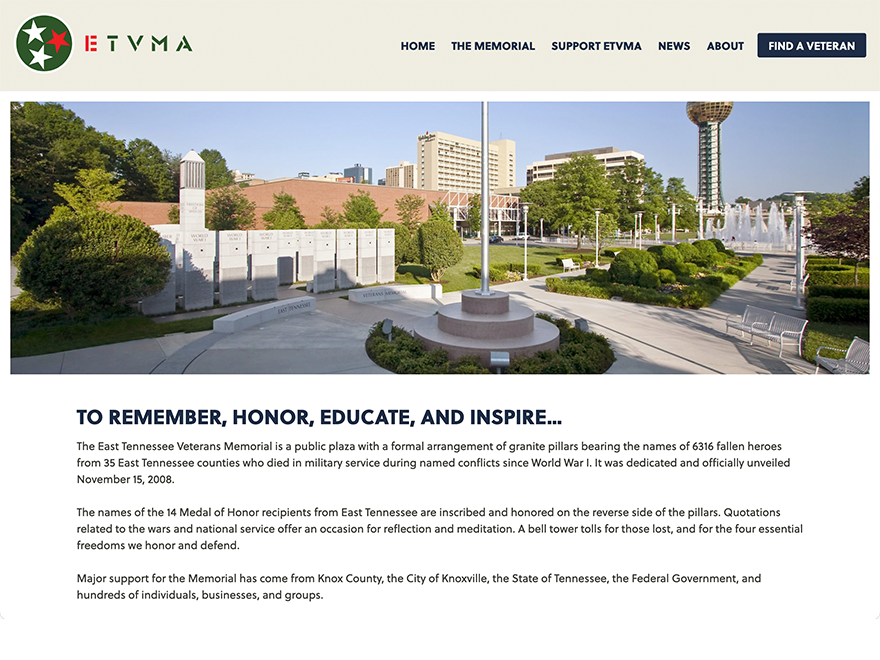

The story behind Knoxville’s East Tennessee Veterans Memorial began in Normandy, France

Bill Felton’s 1990 trip to the Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial in France deeply moved him, the Knoxville News Sentinel reported in 2002. “His visit was so powerful, it instilled in him a determination to come back home and create a memorial honoring fallen veterans of East Tennessee,” the article states.

Felton died in 2011, according to the East Tennessee Veterans Memorial Association website, but he left behind a permanent legacy for Knoxville – and one that’s celebrated by the entire region.

Here’s a look at how the East Tennessee Veterans Memorial came to be established where it now stands at World’s Fair Park.

East Tennessee Veterans Memorial beginnings: ‘It was a labor of love’

Once Felton began taking the first steps on his project, there was no shortage of supporters. Retired News Sentinel senior writer Fred Brown and John Romeiser, at the time a professor at the University of Tennessee, joined Felton on the project, Romeiser told Knox News. Romeiser was previously the association’s board president, and now serves as its historian.

“We had a great discussion. We talked about forming a committee, an organization that would do research. We brought on veterans from World War II and more recent Vietnam – more recent then,” Romeiser said. “It just grew exponentially.”

“It was a labor of love for Bill Felton,” Romeiser added. “He just had that dream. …He was driven. Very good guy, big heart. I learned a lot from him.”

“We want all of the community to be a part of this,” Felton told the News Sentinel in 2003. As it turned out, that was very much the case. Several mayors, state and federal senators expressed support for the memorial, Romeiser said.

It took a few tries to get a final plan for the memorial in place. Initially, it was envisioned to go by the doughboy statue in front of the former Knoxville High School, the News Sentinel reported in 2002. Another proposal suggested a small park on Gay Street, according to Romeiser. The memorial’s eventual location was finalized in January 2006 when the city announced it was donating a portion of World’s Fair Park for the project.

Felton’s inspiration becomes a reality

The memorial, comprised of 32 granite monuments, a flag and bell tower, was constructed between the World’s Fair Park playground and the historic L&N station. Each granite slab displays about 220 names of East Tennesseans who died in military service since the beginning of World War I, according to the website.

Early on, Romeiser helped research the names listed on the memorial alongside Cynthia Tinker, who worked for the University of Tennessee’s Center for the Study of War and Society. “We were building this database. We had about 3000 names initially, and now we have over 6,000,” Romeiser said. “We’re still finding names.”

The memorial was dedicated on Nov. 15, 2008. “We had a lot of veterans there, of course. We had different people in uniform. Huge crowd, lot of dignitaries. It was remarkable,” Romeiser recalled.

The East Tennessee Veterans Memorial will hold its annual reading of the names event this Memorial Day, Monday, May 27, at 6 a.m. at the memorial.

Hayden Dunbar is the storyteller reporter. Email hayden.dunbar@knoxnews.com.

Support strong local journalism by subscribing at knoxnews.com/subscribe.

The influenza pandemic of 1918-1920

Both on the home front and in the combat zones of 1918, the greatest single killer of the Great War was not artillery, machine guns, or poison gas: it was far more insidious and invisible. By some estimates, half of the doughboys, Marines and sailors who died in Europe fell not to enemy fire but to the influenza pandemic of 1918-1920. Sometimes referred to as the Spanish flu, the “plague of the Spanish lady,” and the “grippe,” the epidemic disappeared as quickly as it had appeared by the time the Armistice was signed in November 1918.

On March 11, 1918 the first cases of what would become the influenza pandemic were reported in the U.S. when 107 soldiers rapidly became ill at the Camp Funston training camp in Fort Riley, Kansas. It was the worst pandemic in modern history. The flu that year killed only 2.5 percent of its victims, but more than a fifth of the world’s entire population caught it; it is estimated that between fifty million and one hundred million people died in just a few months. Historians believe at least 500,000 died in the United States alone.

The influenza outbreak swept through military bases in the United States. The virus was an exceptionally deadly strain that struck young, previously healthy adults particularly hard. Once their bodies were weakened, many were vulnerable to secondary infections such as pneumonia, often leading to death. By the late spring, there were influenza outbreaks in fourteen of the largest Army training camps in the United States. After temporarily subsiding, a second more deadly wave of influenza appeared in late summer 1918. By mid-September, it had developed into a mass outbreak. Many servicemen caught the influenza virus in the United States and boarded troopships bound for Europe, unaware of their infected condition. Crowded quarters on the ships provided an ideal environment that readily enabled the flu to spread. Some soldiers did not survive the two-week voyage. Others fell sick during the crossing and were taken directly to hospitals in Britain and France when their vessels entered port.

Healthy soldiers arriving in France in late 1917 and in early 1918 immediately went into battle, distinguishing themselves in infantry charges, artillery exchanges, and trench warfare. However, if they were not already infected by the virus, many contracted it in the close quarters in which they were confined. As has been pointed out, others contracted the disease onboard ship before even arriving in England or France. A third group became ill so quickly in the U.S. that they never had time to go overseas. They died in the field hospitals of their training camps. Others were buried at sea before even reaching land.

A Sampling, by County, of East Tennesseans Who Succumbed to the Flu Outbreak

The Last Great Battle in the Pacific

On 1 April 1945, U.S. ground forces began the Battle of Okinawa. The objective was to secure the island, thus removing the last barrier standing between U.S. forces and Imperial Japan. With Okinawa firmly in hand, the U.S. military could finally bring its full might upon the Japanese, conducting unchecked strategic air strikes against the Japanese mainland, blockading its logistical lifeline, and establishing forward bases for the final invasion of Japan (Operation Olympic), scheduled for the fall of 1945.

The battle, which went into the month of June, was one of the most ferocious of the war with American casualties reaching a staggering 49,151, of which 12,520 were killed or missing. On an individual basis, 24 service members received the Medal of Honor for actions performed during the Battle of Okinawa. Thirteen went to the Marines and Navy corpsmen, nine to Army troops, and one to a Navy officer.

Forty-three (43) East Tennesseans (see names below) gave their lives during the battle with one, Elbert L. Kinser (Greene County), being awarded the Medal of Honor posthumously for his valor and intrepidity.

| Name | Branch | County |

| Ailor, James T. | Army/Army Air Forces | Knox |

| Allen, Hugh H. | Army/Army Air Forces | Sevier |

| Burleson, John B. | Army/Army Air Forces | Monroe |

| Chase, James L. | Marine Corps | Greene |

| Chastain, Houston | Marine Corps | Sullivan |

| Cline, Athel J. | Army/Army Air Forces | Claiborne |

| Cockrum, James A. | Marine Corps | Knox |

| Coffman, John K. | Marine Corps | Roane |

| Cole Jr., Allen W. | Marine Corps | Sevier |

| Colquitt, Herbert R. | Navy | Knox |

| Crowder, Hubert W. | Army/Army Air Forces | Monroe |

| Fleenor, Joseph I. | Marine Corps | Sullivan |

| Goforth, Ernest P. | Army/Army Air Forces | Roane |

| Harris Jr., J. D. | Navy | Hamilton |

| Hill, Abraham L. | Marine Corps | Blount |

| Hoover, Owen E. | Marine Corps | Knox |

| Kennedy, James C. | Army/Army Air Forces | Knox |

| Kinser, Elbert L. | Marine Corps | Greene |

| Kreis, William W. | Army/Army Air Forces | Hamblen |

| Leonard, Woodrow | Marine Corps | Monroe |

| Levi, Eddie L. | Army/Army Air Forces | Hamilton |

| Long, Clarence W. | Army/Army Air Forces | Hamilton |

| Mannon, George | Army/Army Air Forces | Hamilton |

| McCurry, Richard P. | Marine Corps | Knox |

| McDaniel Jr., C. J. | Army/Army Air Forces | Knox |

| Miller, Cyrel E. | Marine Corps | Roane |

| Monds, Jerry S. | Navy | Hamilton |

| Moore, J.C. | Army/Army Air Forces | Roane |

| Mynatt, James P. | Navy | Knox |

| Owens, Kenneth H. | Marine Corps | Blount |

| Palmer, Elbridge W. | Army/Army Air Forces | Sullivan |

| Patterson, Eather E. | Army/Army Air Forces | Blount |

| Poe, John J. | Marine Corps | Hamilton |

| Prince, Hugh P. | Navy | Unicoi |

| Ray, Raymond F. | Marine Corps | McMinn |

| Romines, Robert S. | Army/Army Air Forces | Hamilton |

| Sharp Jr., Floyd J. | Army/Army Air Forces | Knox |

| Stokley, Ernest M. | Navy | Greene |

| Thompson, George E. | Army/Army Air Forces | Roane |

| Vickers, Harold L. | Army/Army Air Forces | Hamblen |

| Waters, Charles E. | Army/Army Air Forces | Johnson |

| Wileman, Mack W. | Army/Army Air Forces | Marion |

| Wolfenbarger, Theodore | Navy | Knox |

The Air War in Europe and the “Bloody 100th”: Some of the “Masters of the Air” From East Tennessee

The story of the air war in Europe during WW II is one of tremendous courage and catastrophic loss. It is the story of US-made B-17 Flying Fortresses and B-24 Liberators, shuttled across the North Atlantic from Canada into Great Britain where they were readied for perilous bombing missions into northern Europe (Occupied France and Hitler’s Germany) between 1943 and 1945.

The 100th Bomb Group (Heavy)—the “Century Bombers” or the “Bloody 100th” as it became known– was among an armada of American bomber and fighter groups forming the Eighth Air Force. This bomb group’s exploits are depicted in the series “Masters of the Air,” currently on Apple TV. Pilots whose planes were not shot down by German fighters or anti-aircraft guns somehow managed to fly their crippled aircraft back to England or Scotland. The death toll of this almost two-year campaign was calamitous. The 100th Bomb Group flew its first combat mission on 25th June 1943 and its last on 20th April 1945. During those 22 months, its air crews were credited with 8,630 missions and the terrible loss of 732 airmen and 177 B-17 aircraft.

Coming from East Tennessee were nine individuals who died during these and other Eighth Air Force missions. All were on B-17s, save Harry R. Wayland who flew in a different type aircraft and James C. Hull who piloted a P-47 Thunderbolt fighter.

Coming from East Tennessee were nine individuals who died during these and other Eighth Air Force missions. All were on B-17s, save Harry R. Wayland who flew in a different type aircraft and James C. Hull who piloted a P-47 Thunderbolt fighter.

A particularly poignant mission was that of the “Varga Venus,” apparently named for the Peruvian-American artist of shapely pin-ups in “Esquire” magazine, Alberto Vargas. Its crew was completing its 26th flight, and John P. Keys from Elizabethton (Carter County) served as pilot along with flight officer and co-pilot, Elvin W. Samuelson. The bomber’s crew included 2nd Lt. Patrick H. Lollis; 2nd Lt. Elton Dickens; Sgt. Frank O. Thomas; Sgt. Harry D. Park; Sgt. Peter P. Martin; Sgt. Gilbert A. Borba; Sgt. Joseph A. Costanza, and Sgt. Donald V. Rieger. Only waist gunner Borba survived after bailing out of the aircraft and being taken prisoner of war. The crew of the “Varga Venus” was typical of such flights. Many had never met before, and the make-up was All-American, with crewmen from states stretching from Vermont to California.

Among the East Tennesseans who fell with the “Bloody 100th” and other units of the “Mighty Eighth” Air Force are the following airmen:

| Name | Branch | County |

| Bennett, George R. | Army/Army Air Forces | Sullivan |

| Clark, Jack L. | Army/Army Air Forces | Hamilton |

| Collingsworth Jr., W. F. | Army/Army Air Forces | Knox |

| Copeland, William J. | Army/Army Air Forces | Knox |

| Hull, James C. | Army/Army Air Forces | Knox |

| Kaylor, Bert E. | Army/Army Air Forces | Hamilton |

| Keys, John P. | Army/Army Air Forces | Carter |

| Norris Jr., Gerkin C. | Army/Army Air Forces | Hamilton |

| Wayland, Harry R. | Army/Army Air Forces | Knox |

The Battle for Iwo Jima

U.S. Marines invaded Iwo Jima on February 19, 1945, after months of naval and air bombardment. The Japanese defenders of the island were dug into bunkers deep within the volcanic rocks. Approximately 70,000 U.S. Marines and 18,000 Japanese soldiers took part in the battle. The Battle for Iwo Jima was an epic military campaign between U.S. Marines and the Imperial Army of Japan in early 1945.

Located 750 miles off the coast of Japan, the island of Iwo Jima had three airfields that could serve as a staging facility for a potential invasion of mainland Japan. American forces invaded the island on February 19, 1945, and the ensuing Battle of Iwo Jima lasted for five weeks. In some of the bloodiest fighting of World War II, it’s believed that all but 200 or so of the 21,000 Japanese forces on the island were killed, as were almost 7,000 Marines. But once the fighting was over, the strategic value of Iwo Jima was called into question.

According to postwar analyses, the Imperial Japanese Navy had been so crippled by earlier World War II clashes in the Pacific that it was already unable to defend the empire’s island holdings, including the Marshall archipelago. In addition, Japan’s air force had lost many of its warplanes, and those it had were unable to protect an inner line of defenses set up by the empire’s military leaders. This line of defenses included islands like Iwo Jima.

Given this information, American military leaders planned an attack on the island that they believed would last no more than a few days. However, the Japanese had secretly embarked on a new defensive tactic, taking advantage of Iwo Jima’s mountainous landscape and jungles to set up camouflaged artillery positions.

Although Allied forces led by the Americans bombarded Iwo Jima with bombs dropped from the sky and heavy gunfire from ships positioned off the coast of the island, the strategy developed by Japanese General Tadamichi Kuribayashi meant that the forces controlling it suffered little damage and were thus ready to repel the initial attack by the U.S. Marines.

Twenty-eight East Tennessee Marines and Sailors died in this five-week campaign — Anderson 1, Blount 2, Cumberland 1, Grainger 1, Greene 2, Hamilton 10, Hawkins 1, Knox 2, Marion 1, McMinn 1, Monroe 1, Sullivan 4, Washington 1.

| Name | Branch | County |

| Bright, Jess W. | Marine Corps | Hawkins |

| Burch, Harold D. | Marine Corps | Blount |

| Byrd Jr, Bernie T. | Marine Corps | Washington |

| Cannon, Ralph E. | Marine Corps | Greene |

| Carver, Clarence J. | Marine Corps | Blount |

| Clasby, Victor E. | Navy | Sullivan |

| Coppock, Cecil A. | Marine Corps | Knox |

| Eldridge, William F. | Marine Corps | Hamilton |

| Foley Jr., James H. | Marine Corps | Hamilton |

| Hass, Oliver | Navy | Marion |

| Helton Sr., Eugene S. | Marine Corps | McMinn |

| Herron, Edward W. | Marine Corps | Knox |

| Kerley, Everett R. | Marine Corps | Cumberland |

| Long, Horace J. | Navy | Grainger |

| Manning, Robert L. | Marine Corps | Hamilton |

| McCaslin, H. Richard | Marine Corps | Monroe |

| McDaniel, Clyde E. | Marine Corps | Hamilton |

| McIntosh, Robert B. | Marine Corps | Greene |

| McMillan, James E. | Marine Corps | Hamilton |

| Moyers, James L. | Marine Corps | Jefferson |

| Musick, Jerrel L. | Marine Corps | Sullivan |

| Mynatt, Andrew D. | Marine Corps | Hamilton |

| Neal, Thomas B. | Marine Corps | Sullivan |

| Russell, Fred O. | Marine Corps | Sullivan |

| Satterfield, William E. | Marine Corps | Hamilton |

| Simmons, William G. | Marine Corps | Hamilton |

| Stewart, Joseph H. | Marine Corps | Washington |

| Walsh, James P. | Marine Corps | Hamilton |

| Wampler Jr., George B. | Marine Corps | Sullivan |

The Vietnam Tet Offensive, January 1968

On February 15, 1968, during some of the heaviest fighting of the Tet Offensive, James T. (Tommy) Davis of Meigs County fell to enemy fire as a result of multiple shrapnel wounds. Six other East Tennesseans died during the campaign. Their bios can be found below.

On the early morning of January 30, 1968, Viet Cong forces attacked 13 cities in central South Vietnam, just as many families began their observances of the lunar new year.

Twenty-four hours later, PAVN and Viet Cong forces struck a number of other targets throughout South Vietnam, including cities, towns, government buildings and U.S. or ARVN military bases throughout South Vietnam, in a total of more than 120 attacks.

In a particularly bold attack on the U.S. Embassy in Saigon, a Viet Cong platoon got inside the complex’s courtyard before U.S. forces destroyed it. The audacious attack on the U.S. Embassy, and its initial success, stunned American and international observers, who saw images of the carnage broadcast on television as it occurred.

Though Giap had succeeded in achieving surprise, his forces were spread too thin in the ambitious offensive, and U.S. and ARVN forces managed to successfully counter most of the attacks and inflict heavy Viet Cong losses.

The Battle of Hue

Particularly intense fighting took place in the city of Hue, located on the Perfume River some 50 miles south of the border between North and South Vietnam.

The Battle of Hue would rage for more than three weeks after PAVN and Viet Cong forces burst into the city on January 31, easily overwhelming the government forces there and taking control of the city’s ancient citadel.

Early in their occupation of Hue, Viet Cong soldiers conducted house-to-house searches, arresting civil servants, religious leaders, teachers and other civilians connected with American forces or with the South Vietnamese regime. They executed these so-called counter-revolutionaries and buried their bodies in mass graves.

U.S. and ARVN forces discovered evidence of the massacre after they regained control of the city on February 26. In addition to more than 2,800 bodies, another 3,000 residents were missing, and the occupying forces had destroyed many of the city’s grand temples, palaces and other monuments.

The toughest fighting in Hue occurred at the ancient citadel, which the North Vietnamese struggled fiercely to hold against superior U.S. firepower. In scenes of carnage recorded on film by numerous television crews on the scene, nearly 150 U.S. Marines were killed in the Battle of Hue, along with some 400 South Vietnamese troops.

On the North Vietnamese side, an estimated 5,000 soldiers were killed, most of them hit by American air and artillery strikes.

“What I saw was probably the most intense ground fighting on a sustained basis over several days of any other period during the war,” Howard Prince, a U.S. Army captain, later told NPR.

“We didn’t know where the enemy was, in which direction even,” Mike Downs, a Marine captain, told NPR.

| Lay, Roger M. |

| McReynolds, George W. |

| Popkin, Steven J. |

| Reed, James E. |

| Ward Jr., John D. |

Battle of Hürtgen Forest

The Battle of Hürtgen Forest (German: Schlacht im Hürtgenwald) was a series of battles fought from 19 September to 16 December 1944, between American and German forces on the Western Front during World War II, in the Hürtgen Forest, a 140 km2 (54 sq mi) area about 5 km (3.1 mi) east of the Belgian–German border.[1] It was the longest battle on German ground during World War II and is the longest single battle the U.S. Army has ever fought.[7]

The U.S. commanders’ initial goal was to pin down German forces in the area to keep them from reinforcing the front lines farther north in the Battle of Aachen, where the US forces were fighting against the Siegfried Line network of fortified industrial towns and villages speckled with pillboxes, tank traps, and minefields. The Americans’ initial tactical objectives were to take the village of Schmidt and clear Monschau. In a second phase, the Allies wanted to advance to the Rur River as part of Operation Queen.

Generalfeldmarschall Walter Model intended to bring the Allied thrust to a standstill. While he interfered less in the day-to-day movements of units than at the Battle of Arnhem, he still kept himself fully informed on the situation, slowing the Allies’ progress, inflicting heavy casualties, and taking full advantage of the fortifications the Germans called the Westwall, better known to the Allies as the Siegfried Line. The Hürtgen Forest cost the U.S. First Army at least 33,000 killed and wounded, including both combat and non-combat losses, with upper estimates at 55,000; German casualties were 28,000. The city of Aachen in the north eventually fell on 22 October at high cost to the U.S. Ninth Army, but they failed to cross the Rur river or wrest control of its dams from the Germans. The battle was so costly that it has been described as an Allied “defeat of the first magnitude,” with specific credit given to Model.[8][9]: 391

The Germans fiercely defended the area because it served as a staging area for the 1944 winter offensive Wacht am Rhein (known in English-speaking countries as the Battle of the Bulge), and because the mountains commanded access to the Rur Dam[notes 3] at the head of the Rur Reservoir (Rurstausee). The Allies failed to capture the area after several heavy setbacks, and the Germans successfully held the region until they launched their last-ditch offensive into the Ardennes.[2][10] This was launched on 16 December and ended the Hürtgen offensive.[1] The Battle of the Bulge gained widespread press and public attention, leaving the battle of Hürtgen Forest less well remembered.

Sixteen East Tennesseans were killed in this brutal conflict. One survivor, now deceased, Command Sergeant Major Ben Franklin with the 16th Regiment, First Infantry Division, described it as the worst fight he experienced during the war: The Hürtgen Forest was an unexplainable mistake of the American General staff, one not to be questioned by simple soldiers. We just obeyed orders. Four divisions took part in the area of the Hürtgen Forest. We had massive casualties out of those four divisions. If you figure the average division normally has 14,000 to 16,000 men in it, but after they’ve been on the line for six months like we had been, we were reduced down to a division, maybe a 10,000 division. So out of 40,000 or 45,000 troops that participated in the Hürtgen Forest, we had 33,000 casualties. You can readily see the impact casualty wise. Now why? One, there were no roads through the forest; there were simply fire trails. Two, the trees were so dense, so close together that you could not even drive a Jeep between them. So everything was on foot, and you had to carry everything, and the weather was miserable!”

Families who lost loved ones have finally gotten closure after decades of uncertainty owing to today’s advanced forensics employed in recent years to identify the remains of these four East Tennesseans, now back home again:

|

|

|

|